| IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION FOR DEPROSCRIPTION | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| BETWEEN: | |||

حركة المقاومة الاسلامية HARAKAT AL-MUQAWAMAH AL-ISLAMIYYAH |

Applicant | ||

| -and- | |||

| SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT | Respondent | ||

| SUBMISSIONS IN SUPPORT OF DEPROSCRIPTION | |||

REPORT ON

SETTLER COLONIALISM, ZIONISM, AND THE GENOCIDE IN GAZA

BY

DR SAI ENGLERT

INTRODUCTION

I have been instructed by Riverway Law to provide a report on matters within my expertise in support of the application to the British Home Secretary to deproscribe Harakat al-Muqawamah al-Islamiyyah (‘Hamas’).

The purpose of this report is to detail the history of settler colonialism during the intense period of European colonialism and how Zionism is a byproduct of that movement. The report connects that history to directly to the continued genocide taking place in Gaza.

QUALIFICATIONS

I give this report in my personal capacity.

I am an Assistant Professor in Middle East Studies, in the Institute for Area Studies, at Leiden University, in the Netherlands.

My research focusses on political economy, settler colonialism, Zionism, and antisemitism.

My academic research has focussed on the Israeli labour movement, its relationship with the Israeli state, as well as with Palestinian and migrant workers. I have published my work on these topics in leading journals in the field such as Middle East Critique, Antipode, The Journal of Palestine Studies, and the Journal of Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies.

7. I have carried out detailed fieldwork research across Israel and Palestine, while based in East Jerusalem, at the Centre of British Research in the Levant. In this context, I have interviewed over 30 respondents from across civil society.

8. I have also published a global comparative study of settler colonialism, stretching the globe and covering the last 500 years, entitled Settler Colonialism: an Introduction. I also co-edited a collection of essays engaging with the current unfolding genocide in Gaza, named From the River to the Sea: Essays for a Free Palestine. My writing has been translated into Turkish, Portuguese, Spanish, Mandarin, French, Dutch, Swedish, and German.

SETTLER COLONIALISM, ZIONISM AND THE GENOCIDE IN GAZA

The situation in Palestine and the wider region is dire beyond words. While the Israeli military increases its assaults in the West Bank and Lebanon, the scale of the genocide in Gaza – ongoing for over a year now – is difficult to capture accurately. In July, a study in the Lancet estimated the combined death toll from direct military assaults, as well as the subsequent famine and rampant spread of disease, at around 186,000.1 A few months later, using the same method, the chair of Global Public Health at the University of Edinburgh, Professor Devi Sridhar, argued that the victims were more likely to surpass a third of a million.2 The internationally renowned Forensic Architecture team published a report in October 2024 titled A Cartography of Genocide, which documented all available individual military actions undertaken by Israel in Gaza since 7 October 2023. Its 827-page long report, came to the conclusion that ‘[t]he patterns … observed concerning Israel’s military conduct in Gaza indicate a systematic and organised campaign to destroy life, conditions necessary for life, and life-sustaining infrastructure’.3

The present text argues that to understand the causes of the unfolding genocide in Gaza and the scale of destruction and murder, it is necessary to place it in the long-durée of Israel’s settler colonial project in Palestine. To do so, is to identify the ongoing historical, social, political, and economic processes that have given rise to the Israeli state and the Gaza Strip, the scale of the refugee population in the latter, and the former’s desire to ‘resolve’ the contradictions they represent. The report proceeds in three steps. It will first define what is meant by settler colonialism; it will then discuss the applicability of the term to Israel on the basis of self-definition by early Zionist and Israeli sources; and it will conclude by applying the model to what we have come to call the Gaza Strip.

What is Settler Colonialism?

Settler colonialism, like all forms of colonialism, is first and foremost a strategy of ‘accumulation on a world scale’, to use Samir Amin’s formulation.4 Settler colonial regimes differ from franchise colonialism – such as British Rule in India or Dutch rule in Indonesia – because they do not limit themselves to militarily controlling conquered territories and their people, in order to extract resources, exploit the local populations, and take advantage of unequal trading relations – although they can, and do, do these things also.

12. Settler colonialism is a colonial process that aims to build lasting societies made up of metropolitan populations – which is to say settlers – that can control territory, stabilise conquest, and rule over the Indigenous peoples it invades, displaces, and dispossesses in the process.5 Settlers settle. They do so in different ways, in different geographical and historical circumstances, and with different levels of success. However, they have in common the fact that they build states, institutions, and social relations on Indigenous land. All settler colonial societies are therefore structured by a fundamental conflict between themselves and the Indigenous people they aim to dispossess, exploit, and/or eliminate.

13. Out of this conflict a whole series of social relations emerge, which have been theorised and discussed in detail: property regimes, which form the backbone of the division between settler and Indigenous populations, and the necessary legal, military, and state apparatus to reproduce them;6 forms of racialization that naturalise settler domination over Indigenous and enslaved populations, as well as the socio-economic differences amongst settlers themselves;7 ideological mechanisms that justify settler rule and encourage the further dispossession, subjugation, and/or elimination of the native populations8; etc.

14. However, studying settler colonialism is not only relevant in trying to understand settler colonies themselves and their inner workings. Indeed, settler colonies play/ed a key role, from the late 15th century onwards, in the emergence and reproduction of the global modern economy through: the extraction and accumulation of land, labour, and resources; the securing of key nodal points in the trade routes of empire; and the extraction of ‘undesirable’ populations for economic, political, or religious reasons (which were often one and the same).

Settler Colonialism and Imperialism

15. The primary purpose of settler – or franchise – colonialism is the accumulation of capital through the extraction of natural resources, the (super-)exploitation of labour, the conquest of land, and the forceful access to new markets. Marx famously summarised this process in his discussion of the role of so-called primitive accumulation in the emergence of capitalism:

The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the aboriginal population, the beginning of the conquest and looting of the East Indies, the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of black-skins, signalised the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production. These idyllic proceedings are the chief momenta of primitive

accumulation. On their heels treads the commercial war of the European nations, with the globe for a theatre.9

16. These different elements of settler/colonial power do not necessarily take place at the same time, but do reinforce one another. The original colonisation of the Americas by European powers, for example, made the accumulation of gold and silver, as well as tobacco, cotton, maize and other agricultural output possible, through the enslavement first of Indigenous populations and later of their African counterparts. This in turn transformed the economic landscape of Europe, strengthening merchants and financiers vis-à-vis de landed aristocracy, and facilitating early industrialisation, which led to shifting internal power balances inside Europe, geographically (from the South to the North East of the continent) and socially (from the aristocracy to the emerging bourgeoisie), as well as between European powers and their rivals across the globe.10

17. In turn, growing European industry, fed by the inputs of the (settler) colonial world, made further and more rapid colonisation possible through increased production, new military, maritime and, later, railway technology. The twin processes of demographic booms and the expropriation of peasant populations that went along with Industrial Revolution also made historically unprecedented numbers of ‘surplus populations’ – those requiring work but unable to be integrated into the labour force – available for settlement. The combination of these factors allowed European powers to force their entry into new territories, overwhelm their populations, and lay claim over their resources, lands, and markets. Once more, the accumulation of capital made possible by these new conquests, further fuelled industry and technological development in the metropole, increasing its reach and accelerating its extractive practices even further.

18. Here, two further aspects of settler colonial power emerge. The first is the role of settler colonies in establishing permanent control of key nodes in the world economy. It is noteworthy that as late as the 19th century, settler colonialism could be understood by European political economists as a the ‘classical’ form of colonialism,11 shedding light on Europe’s need to rely on permanent settlement to project its power around the world. It is only in the advanced stages of the industrial revolution that the balance of power between Europe and the rest of the world was transformed so definitively in favour of the former that it could rule its colonial empires increasingly ‘indirectly’ by moving soldiers, armament, and goods around the world more rapidly.

19. European settlement across the West African Coast, in the Cape and the Falklands, or in North Africa – to name but a few – were founded to secure important strategic points along global trading routes. Populations were settled to secure trade – in goods and people, maintain port infrastructure and defend it from Indigenous resistance, and/or undermine the maritime power of local powers. Growing settler populations and trade infrastructure pushed settlers further inland and increased confrontations with Indigenous populations.12 French settlement of much of Algeria, for example, was the outcome of metropolitan attempts to crush Indigenous resistance to foreign rule, by pursuing them inland – and this despite France’s chronic lack of available settlers.13

20. The last aspect of settler colonialism’s global role worth mentioning here is the way settler colonies made the export of ‘undesirables’ possible, turning the religious, economic, or political unwanted (who often were one and the same) at home into the vanguard of metropolitan power and expansion abroad. In doing so, settler colonialism serves as a pressure valve, diminishing social tensions through the export of surplus populations, while making the latter agents of dispossession across the colonial world.14 The Puritans turned Pilgrims settling in North America, the transformation of the urban poor and early trade union organisers in Britain to Australia, the deportation of the survivors of the Paris Commune to Algeria, are all such examples. Arriving in the settler colony, those oppressed in the Metropole were integrated into the structures of empire and turned into its representatives, displacing and dispossessing Indigenous populations – and creating new surplus populations in the process.15 The latter would either fight back, leading to either victory or savage military repression (and therefore also greater displacement and dispossession), or retreat, increasing the pressure on the resources of the Indigenous populations in those territories, weakening their collective ability to fight back against further settler encroachment.16

21. Finally, this points to a reality that bears repeating in the face of the growing contemporary tendency to minimise the consequences of colonial rule in revisionist writing. These global structures of power were only possible through the continuous exertion of extraordinary levels of violence, both structural and military. While it is not possible to do justice to this topic in full here, suffice it to say that violence is required at every stage of the settler colonial process: to complete conquest, to displace and/or forcibly exploit/enslave entire peoples, to capture land and extract resources, and to crush the inevitable moments of Indigenous resistance and national liberation struggles. The examples abound and are well known: genocides across the Americas and Oceania, the mass murder of Indigenous African and American populations through slavery and forced labour in plantations and mines, the extraordinary amounts of violence meted out in the repression of Indigenous uprisings.17

The Historical Trajectory of the Study of Settler Colonialism

22. The nature of settler colonialism and its specific characteristics have long been the subject of analysis, critique, and debate. It is important to underline this fact. As already pointed out above, contemporary commentators have tried to depict the study of settler colonialism as a new phenomenon, lacking intellectual rigor, and serving as a moral rather than analytical category – especially in relation to Zionism, Israel, and Palestine.18 The facts are quite different. In its modern form, the study of settler colonialism has a long intellectual history that stretches

throughout the second half 20th century. Moreover, as already mentioned above, the issue was hotly debated in the 19th century, under the name of ‘classical colonialism’, amongst political economists in Europe,19 which is to say nothing about how Indigenous thinkers reflected on the colonial powers they encountered and fought.20

23. The first of these modern historical threads is located in Indigenous struggles for national liberation against settler colonial regimes. Palestine was an important locus in the development of this tradition, as was North America. Rana Barakat notes, for example, that in the 1960s and 70s an analysis of Zionist settler colonialism was put forward by a variety of Palestinian authors.21 For example, she points out that Fayez A. Sayegh does so in his Zionist Colonialism in Palestine,22 and that the concept of ‘elimination’, so central to contemporary analyses (see below), was put forward by Rosemary Sayigh in the same period.23 To these examples, could also be added George Jabbour’s comparative study of settler colonialism in Palestine and Southern Africa. In his book, Jabbour defines settler colonialism as:

Once established in their new settlements, the settlers, as befits all colonialists, used to deal with the natives inhumanly. As settler colonialism is different from traditional colonialism because settlers are permanently there, and permanently in contact with the natives, this discriminatory inhuman treatment of the natives has been more systematic, intense and brutal than that which the natives were subjected to by overseas colonialist authorities. Declared espousal of discrimination, on the basis of race, colour, or creed, without the need to feel apologetic about it, is the distinguishing feature of settler colonialism. Because the settlers are well entrenched in the lands they acquire, settler colonialism is not as easy to dismantle as traditional colonialism. The colonialists here were not overseas agents who came to the colonies on duty; they were permanently stationed in the colony, permanently in control of the natives and permanently fortifying their positions of strength.24

24. Here Jabbour develops themes that have remained central to the study of settler colonialism into the present: the enduring presence of settlers, the direct and ongoing conflict between them and the native population, the importance of land and control over it in this process, as well as the centrality of racism in structuring social relations in the settler colonial world. This early indigenous tradition located the importance of studying settler colonies primarily within the context of struggles for national liberation, which had been so successful across the African continent in this period – from Algeria to Angola, from Kenya to South Africa.25 There are also many other Palestinian writers, as Brenna Bhandar and Rafeef Ziadah point out, who have contributed to the development of an analysis of settler colonialism in Palestine (as elsewhere) without necessarily naming it as such.26

25. J Kēhaulani Kauanui makes a similar point in discussing the contribution made by authors, such as Haunani-Kay Trask, Candace Fujikane, and Jonathan Y. Okamura to the study of settler colonialism in Hawaii.27 Moreover, to this list must be added those activists and scholars who were involved in the Red Power movement during the 1960s and 1970s in the United States and Canada. The movement developed in relation to both the civil rights movement and global struggles against colonialism, which reinvigorated the struggle for Indigenous liberation in North America, and found its most famous organisational form in the establishment of the American Indian Movement (AIM). It also laid the foundation for the institutionalisation of Native American and Indigenous studies in the North American context. Some key early contributions here are, amongst many others, Vine Deloria Jr.’s Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto, Paul Chaat Smith and Robert Warrior’s Like. A Hurricane: The Indian Movement from Alcatraz to Wounded Knee, Elizabeth Cook-Lynn Why I can't read Wallace Stegner and Other Essays: a tribal voice, Howard Adams’ Prison of Grass: Canada from a Native Point of View and Jack D. Forbes’ Columbus and other Cannibals.

26. Much like their counterparts in Palestine, these Indigenous scholars developed political and historical analyses of settler colonialism as part of their engagement with Indigenous struggles, history, and intellectual traditions. They also centred the issue of land as key to both their political and scholarly concerns, and prioritised Indigenous epistemologies as the framework for their writings. It was to understand the specific circumstances faced by Indigenous peoples, and thereby participate in the process of liberation itself, that these analyses emerged and were developed.28 In fact, as Omar Jabary Salamanca, Mezna Qato, Kareem Rabie and Sobhi Samour point out, the receding of settler colonialism as an analytical framework to understand Zionism, within the Palestinian context, corresponds to the rise of the Oslo process in the 1990s. As the Palestinian leadership increasingly turned towards (an ever-elusive process of) state building, and in doing so jettisoned the anti-colonial nature of their struggle, so did the analytical framework of settler colonialism fall by the wayside. They write:

[T]he Palestinian liberation movement has seen a series of ruptures and changes in emphasis, and in many ways scholarly production accurately mirrors the dynamics of incoherent contemporary Palestinian politics. Recent Palestinian political history has been a long march away from a liberation agenda and towards a piecemeal approach to the establishment of some kind of sovereignty under the structure of the Israeli settler colonial regime. In this environment, it is not surprising that even scholarship written in solidarity with Palestinians tends to shy away from structural questions.

27. Alongside this literature, a second body of work addressed – roughly in the same period – the issue of settler colonialism, but did so with quite different motivations and approaches. Emerging from, and writing within, largely European academia, historians of empire developed a series of classifications to study and categorise colonial regimes. These approaches were based on identifying broad trends amongst European colonial states and establishing ideal models, within which these could be grouped. The work of D.K. Fieldhouse is exemplary of this approach. A rather conservative figure, Fieldhouse developed such a classificatory system in his The Colonial Empires: A Comparative Survey from the 18th Century.29 First, Fieldhouse divided the colonial world

between ‘colonies of settlement’ and ‘colonies of occupation’. The first were those colonies where Europeans had settled and developed European societies, whereas the latter were those that had been militarily conquered but had not seen the development of a (significant) settler population. In short, he made a distinction between settler and franchise colonialism. Fieldhouse then divided colonies of settlement further into three different categories: pure, mixed, and plantation settlements. These correspond, respectively, to settler colonies that aim to replace Indigenous populations with settlers (North American or Oceanic settlements would fit in this category), settler colonies where minority settler population exploit the majority Indigenous populations (much of the Spanish Empire in the Americas, French Algeria, or British settler colonies in Africa would match this description), and, finally, settler colonies where small settler minorities, such as in the Caribbean or Brazil, exploited a large, overwhelmingly African, imported and enslaved workforce.

28. This approach to settler colonialism has the advantage of recognising the variety of forms of settler domination across the globe and sets out to systematically study them. In addition, Fieldhouse accounted for changes within specific settler colonies, from one form to another. He argued, for example, that while the French initially set up a colony of occupation on the Mediterranean coast of Algeria, they were drawn into the country in an attempt to put down uprisings by the native population. In time, as the amount of land under French control grew, they encouraged the settlements of Algerian land in an attempt to pacify the region. French colonial rule transformed, in the process, into a colony of settlement.30 Similarly, in the case of South Africa, Fieldhouse argues that the struggles between Boer settlers, British colonial powers, and Indigenous resistance transformed the nature of the settlement from pure to mixed.31. While there is a certain elegance to this model-based approach, not least because it facilitates a global comparison between different settler regimes, it also has two important short-comings in comparison with the first approach, discussed above. First, is that it turns the approach developed by Indigenous scholars on its head, starting not with concrete historical situation but with ideal abstract categories. It therefore runs the risk of abstracting the actual social relations that give rise to and shape different settler colonial regimes. Second, and perhaps most importantly, the political aim of liberation, so central to the early theorisations discussed earlier, vanishes from view completely. The approach is then purely historical, consigning Indigenous populations to the past, and remaining largely silent about their ongoing struggles for liberation in the present.

29. The third, and today most popular, approach to the study of settler colonialism is that put forward by Patrick Wolfe, originally in his Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology at the close of the previous century.32 Wolfe’s approach is situated somewhere between the two traditions already discussed. On the one hand, he developed an ideal model for the study of settler colonialism, which considerably limited the applicability of his analysis. On the other hand, Wolfe was very clear about his commitment to decolonisation as well as to the study of the specific structures and methods that allow settler colonies to dispossess and dominate. Central to his contribution has been to bring the genocidal character of settler colonialism to the fore. His approach can be – and usually is – summarised through two of his most famous statements. In his book, mentioned above, he explained that settler colonies ‘were (are) premised on the elimination of the native societies. The split tensing reflects a determinate feature of settler colonisation. The colonizers come to stay — invasion is a structure not an event’.33 In his most quoted text, Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native, he restates this approach in the

following terms: ‘settler colonialism is an inclusive, land-centred project that coordinates a comprehensive range of agencies, from the metropolitan centre to the frontier encampment, with a view to eliminating Indigenous societies’.34

Here the key elements of Wolfe’s approach emerge. First, settler colonialism is not located in the past. It is an ongoing reality, which continues to define settler societies in a diversity of locales, such as North America, Oceania, and Palestine. Second, it is a structural form of domination in which conflict with, and the systematic murder of, Indigenous people should not be understood as isolated or random events. Instead, this is the very nature of settler colonial regimes. Indeed, the third and central claim made by Wolfe is that because settlers challenge Indigenous people’s right to the land, the basis of all collective life, the defining logic of settler colonialism is the elimination of the native. Whether physically, culturally, and/or through assimilation into the settler population, that which differentiates settler colonialism from its franchise counterpart, is the eliminatory drive of settler power, necessary to lay claim on Indigenous land. The strength of this approach is that it allows both the use of a broad comparative framework that can identify similar logics of elimination and domination across the settler colonial world, while simultaneously accounting for the specific ways in which settlers in different places, at different times, dispossess Indigenous populations. Wolfe demonstrates this double ability most elegantly in his Traces of History: Elementary Structures of Race.

However, just as with the other ideal model approach, developed by Fieldhouse and others, Wolfe’s approach, and that of Settler Colonial Studies after him, runs the risk of making reality fit into its theoretical formulation. This is most strikingly true when it comes to the question of elimination. While there is absolutely no doubt that, as the final section of this paper will show, settler colonialism has and continues to be eliminatory in the ways that Wolfe theorises, this alone does not cover the entirety of the settler colonial arsenal of domination. As already touched upon through the work of both Jabbour and Fieldhouse, from very different perspectives, some settler colonies are based primarily on the exploitation of the Indigenous population. This can coexist, as for example in the Spanish settler colonies in the Americas, with eliminatory practices. However, Wolfe and others after him, such as Lorenzo Veracini, precluded this possibility. For example, Wolfe wrote, in explaining the difference between settler and franchise colonies: ‘In contrast to the kind of colonial formation that Cabral or Fanon confronted settler colonies were not primarily established to extract surplus value from indigenous labour. Rather, they are premised on displacing indigenes from (or replacing them on) the land’.35 The issue with this formulation, as should hopefully already be clear, is that Algeria was a French settler colony. Similarly, Veracini, in his Settler Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview, writes: ‘while the suppression of indigenous and exogenous alterities characterises both colonial and settler colonial formations, the former can be summarised as domination for the purpose of exploitation, the latter as domination for the purpose of transfer’.36

This sharp distinction between settler and franchise colonialism on the basis of elimination and exploitation, is difficult to square with reality. Not only are elimination and genocide present across the colonial world,37 but many settler colonial regimes were based primarily on the exploitation of the Indigenous populations. By precluding the possibility of settler colonial regimes being dependent on the exploitation of the Indigenous population, the Wolfe-an model closes off large sections of the settler world from analysis, and ends up focusing overwhelmingly

on the Anglo-settler world – especially Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand – with the partial exception of Palestine.

Shannon Speed has made this point, for example, in relation to the lack of engagement with Spanish settlements in the Americas. She identifies the causes for this absence in the way exploitation is, by definition, located outside of the analytical framework of settler colonial studies. She writes: ‘[i]n places like Mexico and Central America, such labour regimes … were often the very mechanisms that dispossessed indigenous peoples of their lands, forcing them to labour in extractive undertakings on the very land that had been taken from them’.38 Similarly, in his discussion of settler colonialism in South Africa, Robin D.G. Kelley points out that elimination and exploitation went hand in hand: ‘the expropriation of the native from the land was a fundamental objective, but so was proletarianization. They wanted the land and the labour, but not the people — that is to say, they sought to eliminate stable communities and their cultures of resistance’.39

In attempting to resolve the tensions between the theoretical framework and the diversity within the settler colonial world, both Wolfe and Veracini can end up relying on rather awkward formulations. For example, in his Land, Labour, and Difference: Elementary Structures of Race Wolfe states in a footnote: ‘"pure" settler colonialism of the Australian or North American variety should be distinguished from so-called colonial settler societies that depended on indigenous labour (for example, European farm economies in southern Africa or plantation economies in South Asia)’.40 This is only explained in the text through the doctrinal separation between franchise and settler colonialism: ‘[I]n the case of settler colonies, which may also encompass relations of slavery, the colonizers come to stay, expropriating the native owners of the soil, which they typically develop by means of a subordinated labour force (slaves, indentures, convicts) whom they import from elsewhere’.41 Why this must always be the case, or why Southern African ‘so- called colonial settler societies’ are disqualified from being fully settler colonial is not explained. Veracini, on the other hand, in his discussion of Zionist settler colonialism in Palestine, makes a distinction between those Palestinian lands colonised in 1948 and in 1967, characterising the former as settler colonial and the latter as colonial, because the elimination of the native was not achieved in 1967.42 Rana Barakat has convincingly challenged this formulation, not by questioning the centrality of elimination to the settler colonial process, but by pointing to the importance of accounting for specific material circumstances rather than relying on theoretical assumptions.43 It is not that Israel has stopped trying to eliminate Palestinians in the territories conquered in 1967. It is that it has not been able to achieve this goal because of the ‘sheer numbers of Palestinians still present’.44 Settlers are not able to simply impose their goals in a vacuum, they have to engage with the material realities they encounter, not least the Indigenous population and their resistance to colonisation.

Here another danger emerges, which is to collapse settler colonial aims with material realities. For example, if a settler colony aims to eliminate the native – as Barakat discusses in the case of Israel in the West Bank and Gaza – it does not automatically follow that it will be able to achieve this outcome. Indeed, in the process it has to continuously engage with Indigenous resistance,

which can frustrate, delay, or defeat its plans. Jean O’Brien has made a similar point.45 She points out that it is not because settlers desire to eliminate Indigenous populations through miscegenation, for example, that they can achieve this goal. She stresses therefore the difference between ‘the logic of elimination as an aspiration of the coloniser’, and its actual success, continuously challenged by the ongoing resistance of the Indigenous population.46 It is for this same reason – the crucial importance of Indigenous agency – that J. Kēhaulani Kauanui argues for the importance of ‘Indigeneity as a counterpart analytic to settler colonialism’.47 The question of Indigenous agency also relates to the issue of settler exploitation of the Indigenous population. It is striking, for example, that in those settler colonies where settler economies were dependent on Indigenous labour – such as Algeria, South Africa, or Rhodesia already mentioned – the latter were able to mobilise the economic power this gave them within the colonies, in overthrowing settler rule all together. It therefore matters considerably to how one thinks about the stability and longevity of settler colonialism, whether one does or does not exclude those settler regimes that relied on the exploitation of the natives.

Even if one accepts that the logic of settlement is one of elimination in opposition to exploitation – and as argued here it is not clear that one should – the historical record remains that many settler regimes never did overwhelm Indigenous populations through large-scale immigration or importing enslaved populations, and that they therefore remained dependent on Indigenous labour. Those regimes that did – the Anglo settlements in North America and Oceania – where able to do so because of the industrial transformations of the metropolitan economies and the major population transfers this enabled. This also points to the relevance of one last critical note leveraged at settler colonial studies, rather than necessarily at Wolfe directly. In fact, Manu Vimalassery, Juliana Hu Pegues and Alyosha Goldstein have argued that a superficial engagement with Wolfe’s work has led to a flattening of his analysis, thereby facilitating a discussion of settler colonialism in isolation from other historical and material realities, such as different forms of colonialism, imperialism, capitalism, and the specific social relations that these interactions throw up in different times and different places.48 For example, the tendency, they argue, to simply state as a truism that settler colonialism is a structure and not an event, risks stabilising settler colonialism, precluding its moments (events) of failure or defeat.

Zionism and Settler Colonialism

While the historical record, as the pages that follow will detail, is unequivocal on the fact that Zionism is a settler colonial movement and Israel is a settler colonial state, the contemporary political debate is not. Today, despite the presence of nearly 800,000 Israeli settlers – who are recognised as such internationally – in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Golan Heights, it is still a regular occurrence to find authors rejecting the applicability of the label in the Israeli case49 – a tendency that has intensified in the context of Israel’s 2023-2024 genocide in Gaza and the growing international solidarity campaign with the Palestinian people.50

Yet, one would struggle to find such obfuscation in the writings of the early Zionist movement and the Israeli state’s founders. The settler colonial nature of their enterprise was obvious to them and certainly not something to be ashamed of or hidden from view. This should not be surprising – early Zionists were, by and large, (petit-)bourgeois Europeans of the late 19th and early 20th century. Colonialism was to them a perfectly acceptable activity, as was the resolving of internal European political, social, or economic problems through the conquest and settlement of land and the dispossession of peoples, across the world.

Theodore Herzl, the founder of the Zionist Organisation, wrote in his 1896 The Jewish State:

Here two territories come under consideration, Palestine and Argentine. In both countries important experiments in colonisation have been made, though on the mistaken principle of a gradual infiltration of Jews. An infiltration is bound to end badly. It continues till the inevitable moment when the native population feels itself threatened, and forces the Government to stop a further influx of Jews. Immigration is consequently futile unless we have the sovereign right to continue such immigration. The Society of Jews will treat with the present masters of the land, putting itself under the protectorate of the European Powers, if they prove friendly to the plan.51

He continued:

We should there [in Palestine] form a portion of a rampart of Europe against Asia, an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism. We should as a neutral State remain in contact with all Europe, which would have to guarantee our existence.52

The central tenets of Zionism were already clear in these passages of The Jewish State. To succeed in its colonial mission and make state building through settlement possible, the movement would need to address two key issues. It would need to defeat the Indigenous population, who would certainly ‘feel [themselves] threatened’. Relatedly, the Zionist movement would need to secure the backing of an imperial power, whose interests it would serve in return. Both Palestine and Argentina, which Herzl mentions, represented strategic areas in global trade networks that European Empires were vying to control. Other settler populations played the same role in many parts of the world. British settlers in the Falklands, Afrikaner settlers in the Cape, the Pieds Noirs in Algeria; all accumulated Indigenous land in order to defend the trade routes of their empires. In fact, Herzl would discuss the need to learn from different settler colonial projects – from the United States to South Africa – throughout the pages of The Jewish State. There are many other pertinent examples in Herzl’s writings, not least a note he wrote to Cecil Rhodes – the British colonial official who gave his name to the British settler colonies in today’s Zambia and Zimbabwe – urging him to lend his diplomatic support to the Zionist cause. In it, Herzl writes:

You are being invited to help make history ... It is not in your accustomed line; it doesn't involve Africa, but a piece of Asia Minor, not Englishmen but Jews. But had this been on your path, you would have done it by now. How, then, do I happen to turn to you, since this is an out-of-the-way matter for you? How indeed? Because it is something colonial.53

This international settler connection was also made explicit by others. Sir Ronald Storrs, the first British Military Governor of Palestine, for example, explained British support for Zionism in Palestine as the development of a ‘little loyal Jewish Ulster in a sea of potentially hostile

Arabism.’54 The question of the relationship between imperialism, settlement, and repressing Indigenous resistance appears once again at the forefront of the contemporary considerations surrounding Zionism. Decades later, the US Secretary of State Alexander M. Haig put it in these terms: ‘Israel is the largest American aircraft carrier in the world that cannot be sunk, does not carry even one American soldier, and is located in a critical region for American national security’.55

The colonial character of Zionism would repeatedly be made obvious, unsurprisingly, as the movement started making settlement a reality on the ground in Palestine. The Zionist organisation set up the Jewish Colonial Trust (1899), for example, to finance settlement. The latter had been a central concern of Herzl’s in The Jewish State, where he modelled his idea for a ‘Jewish Company’ – as he named it then – on the activities of Rhodes’ British South Africa Company in the Transvaal.56 The Zionist movement’s first collective farms were called Moshavim – a word derived from the Hebrew for colony/settlement: Moshava. The Jewish community in Palestine before 1948 was referred to as the Yishuv – the settlement.

It is also striking, in light of contemporary polemics, to note how long the language of colonisation remained central to the self-presentation of Zionism – and Israel. For example, as Corey Robin has shown, in 1947 the Jewish National Fund could publish a ‘Palestine Picture Book’ aimed at English speaking audiences, which made reference to the ‘Jewish colonisation of Palestine’, ‘Jewish settlers’, ‘Jewish settlement’, and ‘colonists’.57 In a similar vein, but over a decade later, the French-language Israeli daily L’Information d’Israël published a special issue on Franco-Israeli economic relations to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the state’s founding. In it, one finds repeated references to ‘new colonisation’, ‘agricultural colonisation’, and ‘settlers/colonists’ (colons in French)’.58 Strikingly it does in order to describe developments within the border of the state, after 1948, as in this passage: ‘The Department for Agricultural Colonisation of the Jewish Agency is currently in charge of 446 new settlements [colonies] (established after the creation of the state)’. The number of ‘Moshavim’, ‘Kibbutzim’, ‘Nahal settlements’, ‘mid-sized villages’, ‘expansions’ of existing villages and ‘farms and different educational institutions’ that make up these 446 new settlements is then given. The text continues: ‘The lands worked by these new settlers [colons] cover a surface of nearly 150,000 hectares (1,500,000 dunams), which represents half of all the cultivated lands in Israel’.59

The language of colonialism and settlement remained uncontroversial within the Zionist movement for much of its history – including well into the period of statehood. Only with the growing power and victories of national liberation movements around the formerly colonised world did Zionism and the Israeli state attempt to distance itself rhetorically from the language of colonisation, all the while continuing to deepen its practice across historic Palestine.

However, if the colonial nature of Zionism was clear and declared among its adherents from its founding moments, the exact form that its rule over the land and people in Palestine would take, became the theatre for bitter fights amongst the different wings of the Zionist movement in

Palestine during much of the first half of the 20th century. The terms of the debate are interesting here, for two reasons. First, those involved in it actively and self-consciously drew from the lessons of other settler colonies in the development of their strategies for colonisation and settlement in Palestine. Second, the central concern of all the different wings of the Zionist movement was what to do with the Palestinian population and its inevitable resistance to colonisation. The figure of the Indigenous population looms large in these discussions – their land, their labour, their resistance. This centrality also confirms the hollowness of the Zionist slogan that depicted Palestine as ‘a land without a people’ ripe for the taking by ‘a people without a land’.

Two Colonial Strategies

Two broad schools of thought can be identified within the Zionist movement, in the early decades of the twentieth century: Labour Zionism and General Zionism. They would remain the two most important factions of the Zionist movement, up until the end of the 1960s, when Revisionist Zionist would rapidly grow in influence, eventually subsuming the General Zionist. It is important to note how openly these movements discussed their own presence in Palestine in terms of settlement and colonisation, and how freely and openly they drew from other settler colonial projects around the world to develop their own colonial policies.

On the one hand, a bourgeois Zionism took shape early on, and would find its political expression under the banner of so-called General Zionism. Its early expressions are to be found in the writings of Herzl, discussed above, as well as in the activities of some of the movement’s earliest, and most important, financial supporters, such as the French Baron Edmund de Rothschild. The former modelled his ideas for a future state in Palestine on white settlement in South Africa, while the latter preferred the French settler colonial model in Algeria. They imagined that a minority of settlers would own the land and rule over a majority of Indigenous people, whom they would exploit in order to export cheap consumer goods to Europe.60 For these Zionists, the presence of Palestinians was not only acceptable, but necessary – as long as they lived under the boot of their colonial masters. They were to form, like their African counterparts, the basis for the economic sustainability of the future state.

Against this approach, another movement would emerge and eventually conquer the levers of power of the Yishuv. It would remain unchallenged at the helm of its institutions, and then those of the Israeli state, for half a century. The Labour Zionists opposed their bourgeois counterparts on a number of key strategic points. In their minds, the future state would have to be a workers’ one – that is Jewish workers. This would require encouraging Jewish migration to Palestine in much greater numbers (something which remained an issue well into the late 1920s) and the establishment of colonial institutions controlled by the Labour Zionists. The jewel in the crown of the Labour Zionist movement was the Histadrut,61 the Yishuv’s (and then Israel’s) largest trade union federation, which stated in its 1920 founding constitution that it aimed to:

unite all the workers and labourers in the country who live by their own labour without exploiting the labour of others, in order to arrange for all settlement, economic and also cultural affairs of all the workers in the country, so as to build a society of Jewish labour in Eretz Yisra’el. 62

To achieve either goal, the General Zionists would have to be defeated – given that Palestinian workers were more productive (they were used to the local climate, the land, and the physical demands of the work) as well as cheaper, because they made more exploitable by the repression of the British colonial regime. This put newly arrived settlers in the position of having to compete with them, while demanding higher wages for less effective work.63

The Labour Zionist launched what became known as the campaign for ‘Hebrew Labour’, or as the interconnected ‘conquests’ of labour, land, and produce, they aim of which was the development of an ethnically segregated ‘Jewish sector, free of Palestinians.64

They would boycott, picket, and physically assault Palestinian workers in Jewish owned companies their Jewish employers, or those Jewish business owners who sold goods produced by Palestinian workers.65 Out of this struggle a number of key institutions of the Zionist movement, and later the Israeli state, would emerge, such as the Histadrut and the Kibbutzim, and militias like the Haganah that would alter form the backbone of the Israeli army. It should come as no surprise that this campaign was also rooted in deeply racist ideas. As Matan Kaminer and Zvi Ben Dor Benite point out, in the context of Zev Smilansky 1908 essay Hebrew or Arab Workers:

According to Smilansky, Jewish planters preferred Arab workers because they were still in the process of becoming civilized, unlike the Jewish population, and have not raised any concerns or made any demands ... The newly arrived workers are more dedicated to work, but landowners dislike their behaviour and sometimes even consider it dangerous and “suspicious.” Nevertheless, Smilansky argued, Arab workers are lazy, incapable of learning new skills, and untrustworthy. Moreover, as their “savagery comes before their humanity,” Arabs “excel in cruelty to animals,” whereas Jewish workers make sure they are fed on time … As a solution, Smilansky suggested “our brethren” the “Maghrebis, Persians, Yemenis, and poor Sephardim” of the Old Yishuv, non-Ashkenazi Jews who had lived in Palestine for centuries. “We have done some statistics,” he wrote, finding “that many of them would agree to work for low wages.” Moreover, “some of them are quite strong.”’66

The campaign for Hebrew labour was not only defended on the grounds that the (Jewish) workers’ movement should control the future state, however. It was also, its theoreticians argued, the better colonial policy. Haim Arlosoroff, a key figure in the movement, studied colonial policies towards Indigenous workers across the settler world. He found that, although ‘[t]here is almost no example of an effort by a people engaged in settlement’ that could serve as a useful model for the Labour Zionist movement,

the territory of the state of South Africa, and the labour question there, is almost the only instance with sufficient similarity in objective conditions and problems to allow us to compare.67

There too settler workers were outnumbered by their Indigenous counterparts, which he blamed – as he did the Palestinians – for bringing wages down for the settler workers. It was therefore

vital for Jewish workers to organise themselves and develop their institutions and their economy separately from Palestinian workers.

The problem of building an economy that was dependent on Indigenous labour was not only a danger for settler wage levels. It was also clear that the former would rebel and destabilise the settler colony by mobilising their labour power against their colonial rulers. The same mistake should be avoided at all costs in Palestine. The idea of ‘transfer’ – the euphemism for ethnic cleansing used by the Labour Zionists up until the Nakba – emerged out of this vision and would remain the backbone of Labour Zionism.68 If the (Labour) Zionists failed to establish a majority in Palestine, Arlosoroff argued in a 1932 letter to Haim Weizmann – Herzl’s successor at the head of the Zionist Organisation and the future first president of Israel – it would become necessary to envisage:

a transitional period of the organized revolutionary rule of the Jewish minority [...] a nationalist minority government which would usurp the state machinery, the administration and the military power in order to forestall the danger of our being swamped by numbers [of Palestinians] and endangered by a rising. During this period of transition a systematic policy of development, immigration and settlement would be carried out.69

As Zachary Lockman points out, this was quite a visionary prediction, not too dissimilar from the actual developments of the 1947-1949 Nakba.

The danger of developing a colonial economy based on Palestinian labour was brought home powerfully during the Arab Revolt (1936-1939), when Palestinian workers organised a general strike that lasted 6 months, demanding the end of Zionist settlement and British rule. The strike turned into a general military uprising that lasted three years, during which Palestinian guerrillas took control over most of Palestine's urban centres and appeared on the brink of defeating the mighty British empire.70 The Zionists, under the leadership of their labour movement, participated in the uprising’s repression. First, the Histadrut provided strike breakers to defeat the labour stoppages in key industries. Its militias then joined Orde Wingate’s ‘Special Night Squads’, where they were armed and trained before being tasked with guarding key infrastructure against attacks by the revolutionaries, first among which was the Iraq Petroleum Pipeline.71 This episode would prove a key turning point for the fortunes of Zionism and lay the groundwork for the Nakba a decade later: the Palestinian national movement was crushed and politically beheaded by the British, while the Labour Zionist movement emerged better trained, armed, and politically hegemonic within the Yishuv.

There were also other wings in the Zionist movement, of course, although they would remain too minoritarian to deserve mention in this short overview. One exception is the Revisionist movement led by Zeev Jabotinsky. Not only would its militias play an active role in military attacks against the British before 1948, and then during the Nakba, but the Revisionists would become (and remain today) a key political force in Israeli politics, especially after their merger in the 1970s with the General Zionists to form the Likud – Benjamin Netanyahu’s political party. Jabotinsky was as clear sighted as his counterparts in the other wings of the Zionist movement about the

colonial nature of Zionism and the task ahead when it came to the Palestinian population. He famously wrote in his Iron Wall:

There can be no voluntary agreement between ourselves and the Palestine Arabs. Not now, nor in the prospective future. I say this with such conviction, not because I want to hurt the moderate Zionists. I do not believe that they will be hurt. Except for those who were born blind, they realised long ago that it is utterly impossible to obtain the voluntary consent of the Palestine Arabs for converting "Palestine" from an Arab country into a country with a Jewish majority. My readers have a general idea of the history of colonisation in other countries. I suggest that they consider all the precedents with which they are acquainted, and see whether there is one solitary instance of any colonisation being carried on with the consent of the native population. There is no such precedent. The native populations, civilised or uncivilised, have always stubbornly resisted the colonists, irrespective of whether they were civilised or savage.72

Therefore, Jabotinsky argued,

Zionist colonization must either stop, or else proceed regardless of the native population. Which means that it can proceed and develop only under the protection of a power that is independent of the native population— behind an iron wall, which the native population cannot breach. That is our Arab policy; not what we should be, but what it actually is, whether we admit it or not. What need, otherwise, of the Balfour Declaration? Or of the Mandate? Their value to us is that outside Power has undertaken to create in the country such conditions of administration and security that if the native population should desire to hinder our work, they will find it impossible.73

The disagreements between the different wings of Zionism were disagreements about the speed, the intensity, and the nature of conquest, settlement, and colonial rule to be imposed on the Palestinians. It was not about the settler colonial project itself, which they understood, theorised, and implemented. Tracing the back and forth between these different strategies, the conflict between them, and their encounter with Palestinian resistance to their implementation serves as a useful way to make sense of the emergence of what we think of today as the Gaza Strip – and the long trends that have led to genocide.

Gaza and Settler Colonialism

The Gaza Strip is not a naturally defined, self-contained area, nor is it a long-standing socioeconomic region. Certainly not a (quasi)-state. Yet, anyone familiar with Western media coverage of Palestine would be forgiven to think it is any – or all – of the above. The Gaza Strip is, first and foremost, the outcome of 75 years of Israeli settler colonial policy, which has aimed, time and time again, to concentrate as many Palestinians on as little land as possible. Palestinians pushed off their land, during repeated waves of ethnic cleansing, and stopped, by military force, from returning home, found themselves stuck in this enclave. Today, 77% of the strip’s 2.3 million inhabitants are refugees. The strip has been controlled by different states: Britain, Egypt, Israel. Different Palestinian political organisations have enjoyed mass popular support amongst its inhabitants. But one constant remains: the strip’s existence, and its majority refugee population, are permanent reminders of what Palestinians have called the ongoing Nakba, of Israel’s policy of accumulating more land while limiting the Palestinian population on it, and of their failure to make the Palestinian people disappear.

In that sense, the Gaza Strip is not fundamentally different from other areas of large Palestinian concentration across historic Palestine. It is, however, a particularly stark, and cruel, embodiment of Israel’s general policy. For the Israeli state to exist, it must do away with the Palestinian population and their collective claim over the land. This settler colonial logic is on display in a particularly gruesome way in the ongoing, relentless, and US-sponsored, genocide perpetrated by Israel against the Palestinians in Gaza since October 2023. It is the red thread that runs throughout Israeli history – from the Nakba in 1948, to the Naksa in 1967; from the massacres of Deir Yassin, Lydda, and Tantura, to Khan Younis, Sabra and Shatila, and Jenin; from Gaza in 2008, 2012, 2014 to Gaza in 2018, 2021, and today.

The demand for Hebrew Labour – and its twin demand for transfer – was closest to being achieved during the Nakba. Only through raw military power and repression could the newly established state make the slogan real. The Nakba did not emerge suddenly, nor in the heat of battle as Zionist historians have long claimed. It was the outcome of long-term Zionist aims and policies, made possible by the political victory of Labour Zionism within the Yishuv on the one hand, and the crushing of the Palestinian national movement during the Arab Revolt by the British on the other – as outlined above.

Between 1947 and 1949, Zionist militias first, and then the newly formed Israeli army expelled between 700,000 and 800,000 Palestinians, and destroyed around 500 Palestinian villages and urban centres. The refugees were then forbidden from returning - as they continue to be to this day – again debunking the claim that such an immense ethnic cleansing was unintentional.74 The same organisations that had advocated the expulsion of Palestinians from the Yishuv became the central actors of the Nakba and its aftermath. The Zionists-militias-turned-army were central to the expulsion of Palestinians, the dispossession of their goods, and the guarding against so-called infiltrators attempting to return. Palestinian refugees were banned from doing so, while those who remained within Israel’s borders were placed under military rule, only able to leave their areas with a work permit – much like in the West Bank today.

The Histadrut was also a key player, both as part of the body overseeing military rule, and in the distribution (and withholding) of the permits. The Kibbutzim, the Jewish only collective farms, which had first done away with Palestinian workers and Jewish bosses in the beginning of the 20th century, also participated.75 Many soldiers were drawn from the Kibbutzim, and they appropriated much of the most arable land taken from the Palestinians. From 1947 to 1952, the land controlled by the Kibbutzim quadrupled.76 Overall, the UN commission for refugees estimated that the total value of goods and property accumulated through the dispossession of Palestinians in this period was $330 million – over $10 billion in 2002 equivalent value.77 the ’Hebrew Labour’ policy meant ethnic cleansing, dispossession, and redistribution through the institutions of Labour Zionism.

Creation of the Gaza Strip

In the course of the Nakba, Gaza was cut from the villages and agricultural hinterland that formed its wider economic, political, and social world, as well as the centuries old regional trading routes to Egypt, the Hijaz, and the rest of the Levant.78 Instead, Gaza became a refuge for the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians who were running for their lives. Temporary camps, housing the ±200,000 refugees who joined the ±80,000 inhabitants of the area under Egyptian control, grew and solidified as their population was denied the right to return to their homes and lands. Today, of the 2/3 million Palestinians in the Gaza Strip, 77% are refugees, still waiting to return as mandated by international law.

The imperative for Israel became, as it was everywhere across the newly created state, how to establish permanent control over the conquered land, while stopping Palestinians from returning. Two main mechanisms were used. The first was to establish Kibbutzim on the most fertile land, which would serve as both agricultural centres and military outposts. While the Kibbutzim that were attacked on 7 October no longer play the same military role – today the military blockade imposed on the Strip’s population serves that purpose – their strategic role has not disappeared. The Israeli state continues to offer subsidies to its inhabitants to encourage settlement near Gaza, as it does in East Jerusalem and the West Bank.79

Before 1967 and the Israeli conquest of the whole of historic Palestine, the militias of the Kibbutzim clashed directly with the Palestinian fedayeen fighting to return. On one such occasion, which has become famous in Zionist historiography, the head of the Nahal Oz militia was killed. Roi Rotherberg was turned into a symbol of the Israeli state’s struggle against the Palestinians. When Moshe Dayan, a key military and political leader of Labour Zionism, gave his eulogy, he spoke with much clarity about what had happened:

Let us not hurl blame at the murderers. Why should we complain of their hatred for us? Eight years have they sat in the refugee camps of Gaza, and seen, with their own eyes, how we have made a homeland of the soil and the villages where they and their forebears once dwelt. Not from the Arabs of Gaza must we demand the blood of Roi, but from ourselves.80

Rather than abandoning his commitment to preventing Palestinians in Gaza from returning, Dayan concluded that the Israeli state must continue to impose its military control to keep the ‘Gates of Gaza’ shut.

The second mechanism Israel used to control Gaza and the rest of the conquered territories was the construction of ‘developmental towns.’ These towns replaced the ma’abarot, the integration camps where Mizrahim – Jews from the Middle East and North Africa who migrated to Israel – where held, in terrible conditions.81 More often than not these towns were built on top of existing Palestinian villages and cities from which the inhabitants had been expelled, located close to the borders between Israel and its neighbours. While racism prevented these towns from having the same political status as the Kibbutzim, they too guarded against Palestinian return and occupied the land. Instead of agricultural production, the developmental towns were constructed around (single) industries. Among these towns were Ashkelon and Sderot, which were also targeted on October 7.

The ‘Gaza Strip’ was the result of a conscious policy to concentrate as many Palestinians on as little land as possible, outside of the borders of the Israeli state. On the one hand, it was made by the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from their land, and on the other, by Israeli state military, urban, and agricultural policies. This was ‘Hebrew Labour’ in practice: more land and more work for Israeli Jews through the dispossession and expulsion of the Palestinian inhabitants.

From Exclusion to Integration … and Back Again

If the 1948 Nakba attempted to resolve the contradictions of the Zionist colonisation of Palestine, 1967 and Israel’s conquest of the whole of Historic Palestine, as well as the Sinai desert and the Golan Heights, intensified them. The Israeli state reopened the very problems that it had tried to do away with during the Nakba. More land now also meant more Palestinians living under Israeli rule. To employ them was to undermine the policy of Hebrew Labour and increase the structural power of Palestinian workers within the Israeli economy. To refuse to do so was to create a population that was not only politically opposed to Israel’s colonial rule but who’s economic precarity made them all the more likely to rebel.

This contradiction was particularly acute in Gaza, where previous rounds of ethnic cleansing had created a huge Palestinian population on a tiny land mass. Israel’s prime minister at the time, Levi Eshkol, mused post-invasion about the Palestinians in Gaza: “Perhaps if we don’t give them enough water they won’t have a choice [but to leave], because the orchards will yellow and wither.”82 This is the historical root of Israel’s current genocidal campaign, which has, in fact, cut off water, food, and fuel supplies, while calling on the Palestinians to ‘relocate’ into Egypt.

In the immediate aftermath of 1967, the influx of thousands of Palestinian workers, under the control of the military, was seen as a blessing for the Israeli economy. Its expansion post-1948, through a mixture of Western aid and Palestinian dispossession, had been so effective that Israel faced labour shortages, and an internal market too small for its growing economy. The occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (WBGS) created a large captive Palestinian labour force and pool of consumers, alongside new accumulation of land and resources. The occupied territories became dependent on Israel’s labour market: ‘[b]etween 1974 and 1993, 38.4–45.4 percent of the Gaza Strip employed force was employed in Israel, compared to 28–33 percent of West Bank workers.’83 They laboured in manufacturing, care-work, agriculture, and construction. By the mid-1980s, Palestinian workers from the territories represented 7% of the overall Israeli workforce, but 45% in agriculture and 49% in construction.84

While the exploitation of Palestinian workers seemed to resolve Israel’s labour and consumer shortages, it also reanimated the problems that the early labour Zionists had tried to resolve. The first Palestinian intifada of 1987, the largest Palestinian popular movement since the 1930s, brought to life the spectre of their economic power. The Intifada, Israeli closures, and mass mobilisations by Palestinians across historic Palestine caused major disruptions in the industries they dominated.85 In response, there were renewed demands for decoupling the Israeli economy from Palestinian workers – without abandoning the occupied territories.

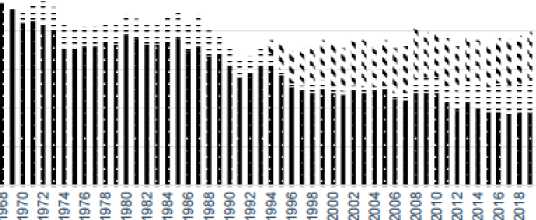

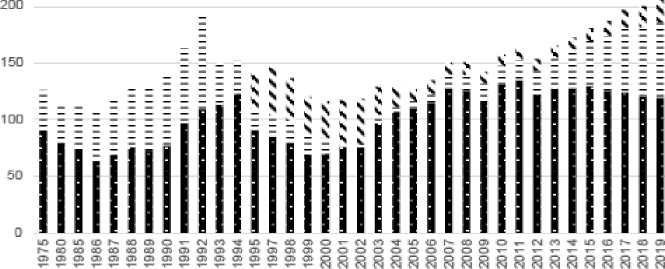

The Oslo process, created the appearance of Palestinian sovereignty over the West Bank and Gaza, while Israel remained in control of the land between and around these islands of supposed autonomy. Settlement in the territories accelerated.86 The granting of ‘Palestinian autonomy’ also allowed Yitzhak Rabin’s government to begin to end the employment of Palestinians from the WBGS inside Israel. Palestinians were replaced by temporary migrant labour, on the model of the Gulf states. The graphs below illustrate the early success, and ultimate limits, of this process in the two industries where Palestinian, and then migrant, workers were concentrated.87 It is worth nothing that the category of ‘Israeli Citizens’ on both graphs should be further divided between Palestinian and Jewish Citizens of the state.

Table ll.a: Employees in the Agricultural Sector, 1980-2019.

* Data generated based on Central Bureau of Statistics Annual Reports.

* Data generated based on Central Bureau of Statistics Annual Reports.

• Israeli Citizens = Palestinian Workers . Migrant Workers

Table H.b: Employees in the Construction Sector, 1980-2019.

Table H.b: Employees in the Construction Sector, 1980-2019.

250

■ Israeli Citizens — Palestinian Workers 2 Migrant Workers

Gaza, smaller and more densely populated than the West Bank, was more dependent on employment in Israel and was particularly hard hit by the new policy. In addition, the ratio between settlers and the rest of the population was immense in Gaza, where 8,000 settlers controlled around 30% of the land, while 1.3 million Palestinians lived on the remaining 70%. Facing even greater deprivation than the West Bank, it is not surprising that Gaza would be a particularly active terrain of Palestinian resistance in the 1990s and early 2000s. Already in 1992, Rabin expressed the ‘wish [that] I could wake up one day and find that Gaza has sunk into the sea’.88 A desire he was not the first, and also not the last, to voice.

Diets and Mowed Grass

The contradictions that conquest, integration, and then decoupling generated have seemed irresolvable for Israeli policy makers, especially in Gaza. While in the West Bank and Jerusalem colonisation advanced apace, the balance of forces in the Strip led to a change in policy. With the end of the second intifada (2000-2005) and under pressure from the military and intelligence

top brass (as well as from the employers in the construction industry), the Israeli labour market was reopened to Palestinian workers from the occupied territories. The hope was that Palestinian workers could be disciplined through the distribution and withholding of work permits, while the incomes generated in Israel would soften (but never resolve) the economic hardships created by the occupation.

More or less simultaneously, however, the decision was made to intensify the decoupling from the Gaza Strip. In 2005, prime minister Ariel Sharon judged that the continued Israeli presence in the Strip was too costly for the meagre strategic benefits. He withdrew soldiers and settlers, and imposed the first blockade of Gaza. Its inhabitants would be ruled from afar, with all vital resources, and all movement in and out of the strip, controlled by the occupier. Not surprisingly in this context, Hamas won the Palestinian elections in 2006 on a platform that rejected the Oslo accords and Fatah’s corruption. Israel, the European Union, and the United States supported Fatah’s coup, which was successful only in the West Bank, which was increasingly integrated into Israel through the expansion of settlements; while Hamas continued to administer a blockaded Gaza.

In response to the humiliation of Fatah, its de facto collaborator in the strip, Israel intensified its blockade. Egypt actively participated in maintaining it, underscoring Arab regimes’ complicity with the Israeli state. Gaza was cut off completely from the rest of Palestine and the region. Two Israeli policies exemplify its practice since 2008. First, Israel, in the words of Dov Weisglass, adviser to prime minister Ehud Olmert, aimed to 'put the Palestinians [in Gaza] on a diet, but not to make them die of hunger’.89 The number of calories allowed to enter the strip were calculated to avoid famine, while avoiding any comfort or stability. Access to Israel’s labour market was virtually ended. The full list of items prohibited or severely limited throughout this period is too long – and absurd – to mention in full. They include at different times: steel and concrete, shampoo and writing paper, feminine hygiene products and diapers, canned tuna and powdered milk.90

The mixture between a total siege by air, land, and water, severe lack of basic goods, and mass unemployment, predictably generated military responses by the different factions of the Palestinian resistance. In response, Israel developed its second policy – ‘mowing the grass’. This euphemism, used freely in Israeli military and political circles, refers to Israel’s regular massacres in the Strip, carried out to collectively punish its inhabitants for resistance to the blockade. For example, Israel killed over 2,200, wounded more than 11,000 and displaced half a million Palestinians in Gaza in 2014. The vice president of the Jerusalem Institute for Strategic Studies, a former Israeli government official and senior fellow in a number of Zionist think tanks, openly mused about whether sufficient violence had been unleashed: ‘Just like mowing your front lawn, this is constant, hard work. If you fail to do so, weeds grow wild and snakes begin to slither around in the brush [sic]’.91

These euphemisms could not hide the horror unleashed day after day on a population of 2.3 million people, crammed into 365 square metres, 77% of whom are refugees, and the majority of whom are children. However, even this level of violence was unable to resolve the contradictions generated by the Israeli settler colonial project – contradictions that were already acknowledged by Zionists over a century ago. Only those drunk on imperial or colonial power

could have been surprised by the fact that this poisoned cocktail would explode, as it did on 7 October 2023. In the words of Saree Makdisi:

what’s most remarkable is that anyone in 2023 should be still surprised that conditions of absolute violence, domination, suffocation, and control produce appalling violence in turn. During the Haitian revolution in the early 19th century, former slaves massacred white settler men, women, and children. During Nat Turner’s revolt in 1831, insurgent slaves massacred white men, women, and children. During the Indian uprising of 1857, Indian rebels massacred English men, women, and children. During the Mau Mau uprising of the 1950s, Kenyan rebels massacred settler men, women, and children. At Oran in 1962, Algerian revolutionaries massacred French men, women, and children. Why should anyone expect Palestinians—or anyone else—to be different? To point these things out is not to justify them; it is to understand them. Every single one of these massacres was the result of decades or centuries of colonial violence and oppression.92

Unresolvable Contradictions

Israel’s genocidal assault on Gaza is only the most recent expression of a long-held desire to ‘disappear’ the Palestinians and resolve the Gaza contradiction. This has been the consistent theme, from the early Zionist fantasy of a ‘land without a people,’ to the ‘conquest’ of labour through ‘transfer’ in the 1920s, to the Nakba, to Eshkol and Rabin’s musings about Gaza — all justifying incessant massacres.

Israeli genocide against the Palestinians emerges out of unresolvable contradictions inherent to its settler colonial project. Unwilling to exploit but unable to eliminate the Palestinians over the long 20th century, Israel finds itself confronted with limited options. (Re)integrating the Palestinians into its economy would revive the spectre of the first intifada – social unrest and the withholding of labour. Keeping the Palestinians under occupation without integrating them in the labour market, increases social tensions and brings back the dangers of the second intifada – sustained military confrontation. Concentrating as many Palestinians as possible in camps, structured around just-not-starvation levels and collective punishment, like in the Gaza Strip, can only lead to more 7 October attacks. The only limits on Israel’s genocidal desires are imposed by Palestinian resistance, regional popular pressure, and international solidarity.

Nor will the unspeakable horror that is being rained down on the Palestinians in Gaza – and now on the population of Lebanon – solve these contradictions. Israel cannot ‘get rid’ of the Palestinians, either through mass murder or expulsion. There is another route of course – that which is mandated by international law and includes the return of the refugees, the end of the military blockade, and equal rights for all the inhabitants between the river and the sea. It is also clear that Israeli policy makers will not consider going that way without considerable pressure being meted out, across the globe.

G. EXPERT OBLIGATIONS

I confirm that I have made clear which facts and matters referred to in this report are within my own knowledge and which are not. Those that are within my own knowledge I confirm to be true. The opinions I have expressed represent my true and complete professional opinions on the matters to which they refer.

I understand that proceedings for contempt of court may be brought by anyone who makes, or causes to be made, a false statement in a document verified by a statement of truth without an honest belief in its truth.

I confirm that I have not received any remuneration for preparing this report.

Sai Englert

Leiden University

The Netherlands

3 December 2024

Khatib, Rasha et al. (2024), ‘Counting the dead in Gaza: difficult but essential’, The Lancet, 404(10449), pp. 237-238.↩︎

Devi Sridhar (2024), ‘Scientists are closing in on the true, horrifying scale of death and disease in Gaza’, The Guardian, 5th September, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/article/2024/sep/05/scientists-death-disease-gaza-polio- vaccinations-israel↩︎

Forensic Architecture (2024), ‘A Cartography of Genocide: Israel’s Conduct in Gaza since October 2023’, Forensic Architecture, 25th October, https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/a-cartography-of-genocide↩︎

Samir Amin (1974), Accumulation on a World Scale: A Critique of the Theory of Underdevelopment, New York: Monthly Review Press.↩︎

Englert, Sai (2022), Settler Colonialism: an Introduction, London: Pluto Press.↩︎

Bhandar, Brenna (2018), Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership, Durham: Duke University Press.Estes, Nick (2019), Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance, London: Verso.Nichols, Robert (2020), Theft is Property! Dispossession and Critical Theory, Durham: Duke University Press.↩︎

Day, Iyko (2016), Alien Capital – Asian Racialization and the Logic of Settler Colonial Capitalism. Durham: Duke University Press.Forbes, Jack D. (1993), Africans and Native Americans: The Language of Race and the Evolution of Red- Peoples, Urbana: University of Illinois Press.Harris, Cheryl I. (1993), ‘Whiteness as Property’, Harvard Law Review, 106(8), pp.1707-1791.Karuka, Manu (2019), Empire's Tracks: Indigenous Nations, Chinese Workers, and the Transcontinental Railroad. Oakland: California University Press.Mamdani, Mahmood (2012), Define and Rule – Native as Political Identity, Cambridge: Harvard. Wolfe, Patrick (2016), Traces of History: Elementary Structures of Race, London: Verso.↩︎

Barakat, Rana (2018), ‘Writing/righting Palestine Studies: Settler Colonialism, Indigenous Sovereignty and Resisting the Ghost(s) of History’, Settler Colonial Studies, 8(3), pp. 349-363.